TAMAHNOUS

[ta-MAH'-no-us] or [tam-án-a-was] or [tamá-nawas] or [tah-MAH'-na-wis] — noun, verb, adjective

Meaning: Spirit; Guardian spirit; Personal Spirit; Ghost; Goblin; Witch; Magic; Luck; Fortune; Slight of hand; One's particular forte, specialty, or strength

Origin: Several possible, perhaps convergent etymologies:

Chinook, itamánawas 'guardian or familiar spirit; magic, luck, fortune; anything supernatural' >i-ta-mánwash (spirit creature)

Sahaptin tamánwit ‘law, government’, esp. that of Nature as spelled out by Coyote, the mythological emissary of the creator and law-giver, who was known as tamanwilá > tamánwi ‘create, ordain’

Nimipuutímt tamálwi ‘lead, plan, legislate’

A word with multiple spellings and slight pronunciation variation, including, but not limited to: tomahnous, tamanass, tahmahnawis, tamánawas, tamanawass, and tamanawaz [This document will use the slightly more common ‘tamahnous’ for sake of clarity] to describe some form of spiritual or supernatural power. It is a concept similar in many ways to that of wakd or mahopa of the Oceti Sakowin; manitowi of the Algonquin; pokunt of the Shoshone; orenna or karenna of the Mohawk, Cayuga, and Oneida; urente of the Tuscarora; the iarenda or orenda by the Huron; kami of the Japanese; kamuy of the Ainu; fylgja or hamingja of the Norse; and mana of the Melanesian and Polynesian cultures.

One’s “tamahnous” can be their guardian spirit, who gives them their strength, or can be an evil spirit out to steal one’s soul. The word is used as a noun, a verb or as an adjective according to whether it means a spirit is invoking the supernatural, or is ascribing magic powers either to men or to some object used as a charm.

An invective level one step higher than “mesachie”, when used to mean "bad". “Mesachie tamahnous” (demon, fiend, witchcraft, necromancy) was a title usually assigned to an evil spirit of some kind, as seen in the expression "klale tamahnous" (black magic, the Devil).

A sudden or unseasonal storm might be referred to as a “tamahnous wind” (preternaturally big wind, very bad storm), while a particularly vile imperialist might be referred to as “tamahnous whiteman” (damned whiteman; devilish whiteman)

However, “tamahnous” also has a general (and potentially benign) meaning associated with magic or the supernatural that need not convey evil or malice, whereas “mesachie” has no such supernatural context and is always evil or malicious. People were often aided or helped by a “kloshe tamahnous” (good spirit). Traditional healers would “mamook tamahnous” (conjure, make magic) to cure many ills, and the title “tamahnous man” (sorcerer, wizard, conjurer) would be applied to an indigonus doctor or ‘medicine man’.

The book Ten Years in Oregon (Daniel Lee & Joseph H. Frost, 1844) features two references to the word:

It is firmly believed that [medicine-men] can send a bad “tam-an-a-was” into a person, and make him die.

[...] there were but two men in the whole clan that had the Elk “tamanawas,” that is, the spirit of the elk hunter.

There also exists a Chinookan word that made its way into Chinook Wawa, “tah” (a spirit; supernatural thing or person), which together with “tamahnous” appear in The Forgotten Tribes: Oral Tales Of The Teninos And Adjacent Mid-Columbia River Indian Nations (Donald.M. Hines, 1991). An excerpt, collected April 1921 from an unknown informant, sheds some possible light onto the concept of “tamahnous” as a personal spirit power:

A band of Umatilla hunters were in camp. A great eagle was soaring, circled and soared overhead, far up in the skies. An aged Tahmahnawis man was challenged to bring down the eagle with his Tah.

He said: “I can do that.” The old hunter “shot” his Ta hmahnawis at the bird, but to no purpose. The eagle continued soaring.

It was then that a younger man said: “You are too old. You cannot kill the eagle with your Tahmahnawis power. I will now kill the eagle with my power.”

Suiting action to his words, the young man “shot” his tahmahnawis at the eagle which immediately came tumbling down through the air, falling dead neart the camp. The aged Indian made no comment. He had been beaten by his younger companion.

Early observers usually referred to these spirit powers by the Chinook Jargon term tamahnous, as in “tamahnous dancing” or “tamahnous spirit”. In the rather biased document Ten Years Of Missionary Work Among The Indians at Skokomish, Washington Territory (Myron Eells 1886), “tamahnous” is described at great length, stating:

Another great difficulty in the way of their accepting Christianity is their religion. The practical part of it goes by the name of ta-mah-no-us, a Chinook word, and yet so much more expressive than any single English word, or even phrase, that it has almost become Anglicized. Like the Wakan of the Dakotas, it signifies the supernatural in a very broad sense. There are three kinds of it.

Black Tamahnous Rattle.

First. The Black Tamahnous. This is a secret society. During the performance of the ceremonies connected with it, all the members black their faces more or less, and go through a number of rites more savage than any thing else they do. They do not tell the meaning of these, but they consist of starving, washing, cutting themselves, violent dancing, and the like.

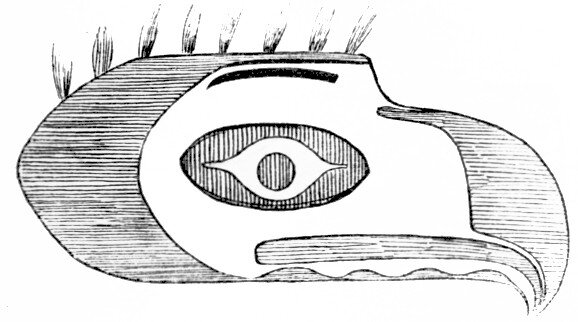

Bird Mask Used in the Black Tamahnous Ceremonies by the Clallams.

It was introduced among the Twanas from the Clallams, who practiced it with much more savage rites than the former tribe. It is still more thoroughly practiced by the Makahs of Cape Flattery, who join the Clallams on the west. It was never as popular among the Twanas as among some other Indians, and is now practically dead among them. It still retains its hold among a portion of the Clallams, being practised at their greatest gatherings. It is believed that it was intended to be purifical, sacrificial, propitiatory.

Swine Masks Used in the Black Tamahnous Ceremonies by the Clallams.

Second. The Red, or Sing, Tamahnous. During the performance of its ceremonies, they generally painted their faces red. It was their main ceremonial religion. During the fall and winter they assembled, had feasts, and performed these rites, danced and sang their sacred songs; it might be for one night, or it might be for a week or so. Sometimes this was done for the sake of purifying the soul from sin. Sometimes in a vision a person professed to have seen the spirits of living friends in the world of departed spirits, which was a sure sign that they would die in a year or two, unless those spirits could be brought back to this world. So they gathered together and with singing, feasting, and many ceremonies, went in spirit to the other world and brought these spirits back.

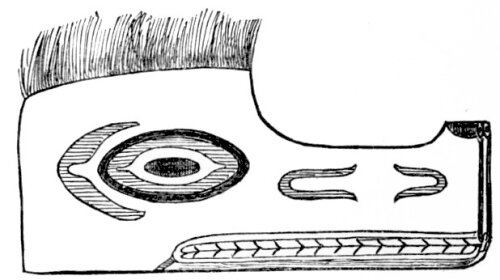

Mask Used in the Black Tamahnous Ceremonies by the Clallams.

[The markings are of different colors. The wearer sees through the nostrils.]

This spirit-world is somewhere below, within the earth. When they are ready to descend, with much ceremony a little of the earth is broken, to open the way, as it were, for the descent. Having traveled some distance below, they come to a stream which must be crossed on a plank. Two planks are put up with one end on the ground and the other on a beam in the house, about ten feet above the ground, in a slanting direction, one on one side of the beam, and the other on the other side, so that they can go up on one side and down on the other. To do this is the outward form of crossing the spirit-river.

If it is done successfully, all is well, and they proceed on their journey. If, however, a person should actually fall from one of these planks, it is a sure sign that he will die in a year or so. They formerly believed this to be so, but about twelve years ago a man did fall off, and did die within a year, so then they were certain of it. Having come to the place of the departed spirits, they quietly hunt for the spirits of their living friends, and when they find what other spirits possess them, they begin battle and attempt to take them and are generally successful. Only a few men descend to the spirit-world, but during the fight the rest of the people present keep up a very great noise by singing, pounding on sticks and drums, and in similar ways encourage those engaged in battle. Having obtained the spirits which they wish, they wrap them up or pretend to do so, so that they look like a great doll, and bring them back to the world and deliver them to their proper owners, who receive them with great joy and sometimes with tears of gratitude. At other times they go through other ceremonies somewhat different. This form has now mostly ceased among the Twanas, but retains its hold among a large share of the Clallams. The Christian Indians profess wholly to have given it up.

Black Tamahnous Mask.

Third. The Tamahnous for the sick. When a person is very sick, they think that the spirit of some bad animal, as the crow, bluejay, wolf, bear, or similar treacherous creature, has entered the individual and is eating away the life. This has been sent by a bad medicine-man, and it is the business of the good medicine-man to draw this out, and he professes to do it with his incantations. With a few friends who sing and pound on sticks, he works over the patient in various ways.

This is the most difficult belief for the Indian to abandon, for, while there is a religious idea in it, there is also much of superstition connected with it. As the Indian Agent at Klamath, Oregon, once wrote: “It requires some thing more than a mere resolution of the will to overcome it.” “I do not believe in it now,” said a Spokane Indian, “but if I should become very sick, I expect I should want an Indian doctor.” It will take time and education to eradicate this idea. It is the only part of tamahnous, which I think an Indian can hold and be a Christian, because it is held partly as a superstition and not wholly as a religion. Some white, ignorant persons are superstitious and, at the same time, are Christians. The bad spirit which causes the sickness is called a bad tamahnous. Soon after I first came here, we spent several evenings in discussing the qualifications of church membership, the main difference of opinion centering on this subject of tamahnous over the sick. I took the same position then that I do now, and facts seem to agree thereto; for, among the Yakamas, Spokanes, and Dakotas, who have stood as Christians many years through strong trials, have been some who have not wholly abandoned it, it remaining apparently as a superstition and not a religion.

Additional information can be gleaned from the book Life at Puget Sound: with sketches of travel in Washington Territory, British Columbia, Oregon & California (Caroline C. Leighton,1884), which details some cultural practices centered around the concept of “tamahnous”:

AUGUST 2, 1865.

We went this morning to an Indian Tamáhnous (incantation), to drive away the evil spirits from a sick man. He lay on a mat, surrounded by women, who beat on instruments made by stretching deer-skin over a frame, and accompanied the noise thus produced by a monotonous wail. Once in a while it became quite stirring, and the sick man seemed to be improved by it. Then an old man crept in stealthily, on all-fours, and, stealing up to him, put his mouth to the flesh, here and there, apparently sucking out the disease.

APRIL 30, 1866.

In the winter we were told, that, when the spring came fully on, the Indians would have the "Red Tamáhnous," which means "love." A little, gray old woman appeared yesterday morning at our door, with her cheeks all aglow, as if her young blood had returned. Besides the vermilion lavishly displayed on her face, the crease at the parting of her hair was painted the same color. Every article of clothing she had on was bright and new. I looked out, and saw that no Indian had on any thing but red. Even old blind Charley, whom we had never seen in any thing but a black blanket, appeared in a new one of scarlet.

NOVEMBER 20, 1866.

To-day we met on the beach Tleyuk (Spark of Fire), a young Indian with whom we had become acquainted. Instead of the pleasant “ Klahowya” (How do you do?), with which he was accustomed to greet us, he took no notice of us whatever. On coming nearer, we saw hideous streaks of black paint on his face, and on various parts of his body, and inquired what they meant. His English was very meagre; but he gave us to understand, in a few hoarse gutturals, that they meant hostility and danger to any one that interfered with him. We noticed afterwards other Indians, with dark, threatening looks, and daubed with black paint, gathering from different directions. The old light-keeper was launching his boat to cross over to the spit, and we turned to him for an explanation. He warned us to keep away from the Indians, as this was the time of the “Black Tamáhnous,” when they call up all their hostility to the whites. He pointed to some Indian children, who had a white elk-horn, like a dwarf white man, stuck up in the sand to throw stones at. I had noticed for the last few days, when I met them in the narrow paths in the woods, that they stopped straight before me, obliging me to turn aside for them.

These practices invoking, venerating, and practicing “tamahnous” were directly targeted by the Canadian government, as seen in the third section of the 1876 Indian Act, a totalitarian law of repression which declared that:

“Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the "Potlatch" or in the Indian dance known as the "Tamanawas" is guilty of a misdemeanor, and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than six nor less than two months in any gaol or other place of confinement; and every Indian or persons who encourages ... an Indian to get up such a festival ... shall be liable to the same Punishment.”

Today the word (and its many spellings) lends itself to a variety of place names and institutes:

Tomahnous Peak, located on the southeast side of the Tatshenshini River, on the divide between Tomahnous Creek and the Tkope River in British Columbia.

Tamanawis Secondary is a public secondary school located in in Surrey, British Columbia.

Tamanawas Falls forms a broad curtain where Cold Spring Creek thunders over a 33.5 meter (110-foot) lava cliff near the eastern base of Mount Hood in Oregon.

Tamanos Mountain is a 2,069.5 meter (6,790-foot) summit located in Mount Rainier National Park in Washington.

The Tamahnous Theatre Workshop Society (later Tamahnous Theatre) in Vancouver, British Columbia was founded in 1971 by John Gray. It specialized in experimental theatre, particularly collective creation. Following the theatrical principles of Polish director Jerzy Grotowsky, Tamahnous (a Chilcotin work for magic), experimented with form and focused on inner experience realized through visual images. By 1981, Tamahnous had produced 38 plays, 21 of which were original. The first shows were performed in the Vancouver Arts Centre. When Larry Lillo succeeded John Gray in 1974, the company relocated to the Vancouver East Cultural Centre. The company eventually closed in the mid-90s, but the Tamahnous Archives are housed at Simon Fraser University Library in Burnaby, British Columbia.

![Mask Used in the Black Tamahnous Ceremonies by the Clallams.[The markings are of different colors. The wearer sees through the nostrils.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/599f4601e3df283ad2ee5d10/1603770763763-36565220GMQXRLINDCFB/Mask+Used+in+the+Black+Tamahnous+Ceremonies+by+the+Clallams..jpg)